Lin Ottinger has spent more than half a century unearthing rare gems, fossils and dinosaur bones hidden beneath Utah’s rugged, rust-hued landscape.

Lin Ottinger sat on a folding chair behind the counter of his eponymous rock shop in Moab, Utah, a cattle dog to his right, telling a customer about the time he traded a dinosaur bone for six dinosaur eggs with a man from China.

“How much for the eggs?” the customer asked, nodding towards a display case.

“Not for sale,” Ottinger replied in a raspy voice. “Those are for my personal collection.”

The fossilised embryos look like a prop from the set of Game of Thrones, but they fit right in with the Dugway geodes, ammonite fossils and a $2,900 apatosaurus femur replica modelled after the one he bartered for the eggs. “Only serious buyers may tap on this!” warns a handwritten sign affixed to the bone.

Moab has long attracted adventurers (Credit: Henk Meijer/Alamy)

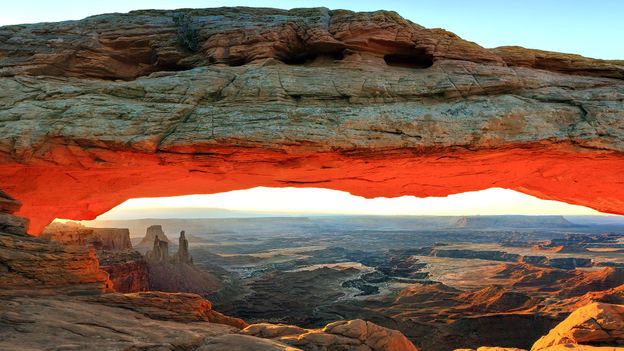

Ottinger, 89, is a symbol of old Moab, a place that has long attracted warring factions of adventurers, from Mormon explorers and hard-living cowboys, to prospectors and conservationists. But Moab is mining new riches now, with record numbers of avid rock climbers, mountain bikers, hikers and 4X4 enthusiasts visiting its two surrounding national parks, Arches and Canyonlands. The fever pitch makes many people wonder if the town can hold on to its rugged charm.

No-one symbolises that charm better than Ottinger, a living testament to what Moab was – and maybe still is; a place for swashbucklers who favour the natural world over mainstream civilisation.

“He definitely is the original mountain guy of Moab, who knows the land and opened it up to people on his tours,” said retired special effects technician Chris Burton, who met Ottinger on a film location that Ottinger scouted in the 1980s. (Because Ottinger is so familiar with the landscape, he has often been asked to guide film crews to camera-ready scenery.)

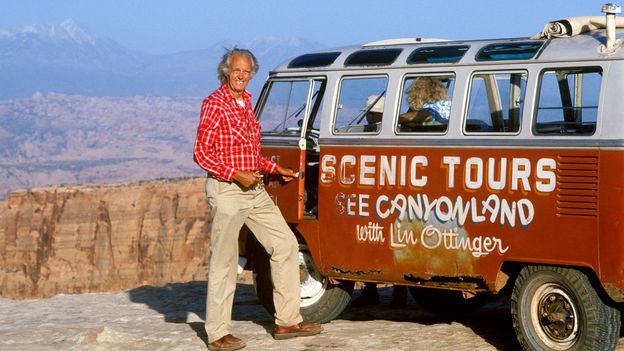

Until the 1980s, Ottinger took tourists in vans to explore the Canyonlands (Credit: Visions of America/Getty)

From 2014 to 2015, visitation to nearby Arches National Park increased by more than 100,000 sightseers. Last year, that surge nearly doubled. Canyonlands National Park, just a few miles further up Highway 191, saw numbers spike by more than 141,000 people in 2016. It’s common to queue for hours to enter the parks on peak summer weekends.

Formerly a dusty strip lined with empty lots and abandoned buildings, Moab’s main road is now dotted with chain hotels and bike rental shops. Sandwiched between them is Lin Ottinger’s Moab Rock Shop. The store and museum, more than half a century old, is filled with vintage curios: logs of petrified wood; acid-etched horn coral fossils from a formation just north of town; and antique drilling rigs once used to extract oil and uranium.

Just as it did other prospectors, uranium drew Ottinger to town in the early 1950s. He, however, was pulled by something more than the dream of striking it rich. Shortly after Ottinger was released from a two-year stint as an army mechanic, he was offered a job felling timber in northern California. With around a month to kill before his start date, Ottinger, a lifelong geology enthusiast – he started collecting and selling quartz rocks and Native American arrowheads when he was about five years old in Tennessee – decided to check out a metal and gem show in Boise, Idaho.

Charmed by Moab, Ottinger moved to the town in the early 1950s (Credit: Doug Pensinger/Getty)

There, someone showed him a chunk of andersonite, a vivid yellow-green mineral found in uranium deposits. The man told Ottinger he’d found the rare gem in Kane Creek in Moab, Utah.

Ottinger packed up his wife and kids and headed south from their Oregon home. As he approached the small town in southeastern Utah, he was awestruck by the towering red spires, snow-capped peaks and burnt sienna- and jade-striated rock walls.

“I thought that was the prettiest thing I had ever seen,” he said.

Ottinger never made it to California. Instead, he got a job driving trucks for the mines. “I said, ‘I’ll stay here and see the country as long as I can’.”

In the late 1950s, as the uranium boom faded and the hordes of prospectors deserted town, Ottinger transitioned back to his original childhood business: selling rocks.

Over the years, the self-taught geologist and palaeontologist has made some impressive finds, including the toe bone of a utahraptor, a large percentage of an euoplocephalus and a well-preserved apatosaurus, which Ottinger claims is the most complete to be found in the US. He donated many of his findings to the late Dr James Jensen at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah. When Ottinger discovered a new species of dinosaur in the 1970s, Jensen named the 30ft-long, 7-ton ‘iguanodon ottingeri’ after him.

Over the years, the self-taught palaeontologist has made impressive finds in Moab (Credit: Gabbro/Alamy)

When Ottinger opened his shop in 1960, tourists started asking to tag along on his explorations. One woman requested 86 different tours for 86 days.

“Why do they have Easter egg hunts? Because everyone likes to look for something,” he said. “They want to find something.”

On Ottinger’s early fossil excursions, tourists did find things: gem-quality agates, marine fossils and dinosaur bones. When Ottinger was told he could no longer collect dinosaur fossils from public lands, he took people hunting for invertebrate fossils and rocks, before transitioning into geology-focused sightseeing tours.

Until Ottinger retired from the tour business in the 1980s to focus on his shop, he hauled visitors in a fleet of Volkswagen vans to remote sites throughout Canyonlands (like rose-painted Angel Arch and the striated spires called the Needles) and Gemini Bridges in Arches before either were designated a national park. Tapping into his deep knowledge of the processes that transformed the Earth’s crust over time, he explained rock colours, formations and evolution of the surrounding land.

“There’s so much to see. You can’t see it in two lifetimes” (Credit: Henk Meijer/Alamy)

Today, there are around 60 tour operators in the area, employing countless guides for wide-ranging escapades, from river rafting and canyoneering to mountain biking and jeep excursions. To Ottinger, there’s plenty of room for all of them. And after 62 years of exploring the land, even he still feels like he hasn’t seen everything.

“There’s so much to see,” he said. “You can’t see it in two lifetimes.”

Join over three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.